Plantar Fasciitis

The word “plantar” refers to the sole of the foot. “Fascia” is a thick connective tissue (like gristle) on the sole of the foot that helps support the arch.

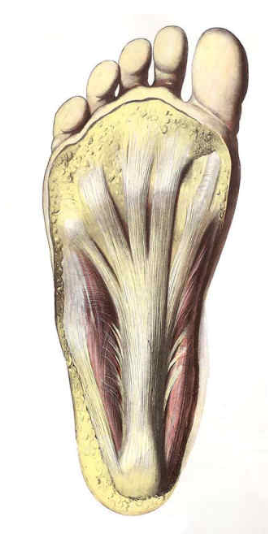

In the drawing to the left, you can see what the plantar fascia would look like if you took of the skin and fat from the sole of the foot.

This structure is like the string on a bow (think bow and arrow), where the string helps support the arch (bow shape).

The stress on this fascia, which helps support the arch structure of the foot, is spread over a wide area in the forefoot as it inserts at the bases of the toes, but is concentrated at its insertion in the heel bone (calcaneus).

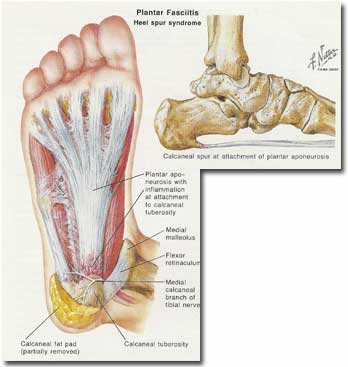

A small tear can occur at the insertion of this fascia near the heel, where the stress on this fascia is focused on a smaller area. The local tissues react to this overload (which is a low grade injury) of this fascia tissue, and cellular events we know of as inflammation (swelling, pain, warmth, sometimes redness) will occur.

The suffix “itis” refers to inflammation of that part. Therefore, fasciitis means inflammation of the fascia.

As part of the healing process, the body makes repair tissue. Since the injury or tear is occurring right where the fascia attaches to the heel bone, often as part of the repair process, a small bit of bone is formed in this repair tissue. This bone can be seen on the xray as a small heel spur.

The spur itself is not dangerous and is not sticking into the ground, but indicates that the body is trying to repair an injury in this area.

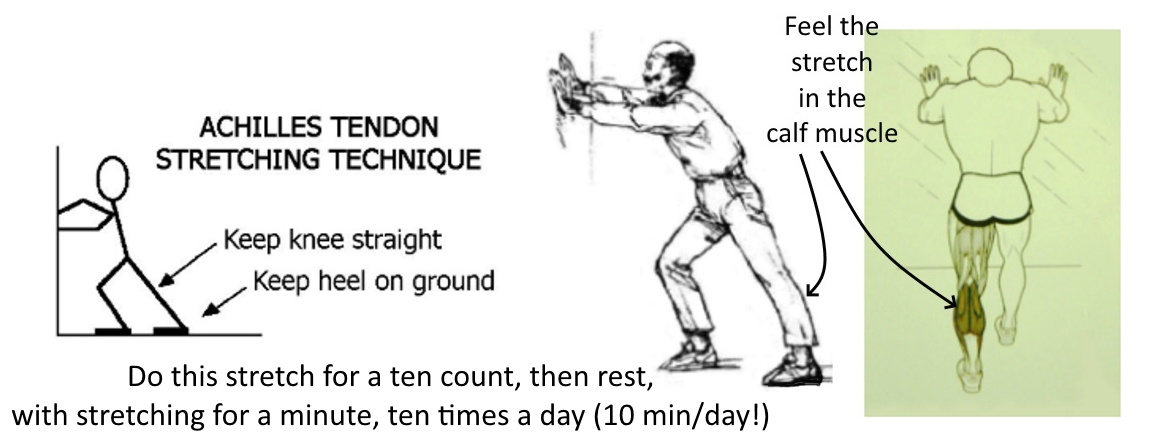

The principles of treatment involve stretching the tissue (in this case Achilles and plantar fascia) for more flexibility, so the plantar fascia can heal.

Technique notes: The symptomatic side, the one to be stretched, is farther from the wall, with the foot flat on the ground. The side not being stretched has the knee bent in front. The stretch will be felt in the calf muscle.

Things to avoid:

–lifting back heel off ground

–bouncing (keep sustained stretch)

–rotating back foot outward (keep toes pointed to the wall).

Another technique, here to the right: keep the ball of your foot on a step, and let your heel come down towards the floor, with your body weight causing the stretch. -->

Since the plantar fascia injury can catch up on the healing when the patient is at rest (sitting for a while, sleeping), often some of the heel pain can be minimized by the type of stretching shown here to the right. This stretch is helpful before putting your foot on the floor in the morning.

The technique involves trying to stretch the toes and ankle upwards. Usually, the plantar fascia can be felt and massaged. The stretch needs to be done for about a minute.

As another option, the plantar fascia can be kept in a stretched position by use of a splint worn at night when sleeping.

These types of splints can be purchased usually online by searching for “plantar fascia night splint” or similar terms, and usually cost under $25.

With conservative treatment, improvement will usually occur, but slowly, often taking at least 6 weeks before significant improvement is seen.

Some patients ask about injections, but this treatment is not my first choice. The injection is painful, and the results are temporary, although in some cases, there may be some benefit.

On occasion, when non-surgical treatments have failed, surgery is required. In those cases where the patient chooses surgery, the recovery would involve being on crutches or using a walker (avoid full weight bearing) for at least six weeks. The good news is that vast majority of patients improve without needing an operation.